- Home

- David B. Axelrod

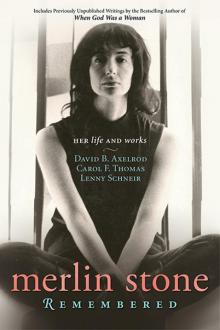

Merlin Stone Remembered Page 4

Merlin Stone Remembered Read online

Page 4

Albright Knox Annual Sculpture Award (also awarded in 1965).

Interest in ancient religions begins to influence her artwork and thinking.

1963–64

Divorced and moved to a farmhouse in upstate New York, where she continued to sculpt and exhibit her work.

1965

Returned to Buffalo, NY, and continued work as a sculptor.

Taught children’s creative arts classes at Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo.

Completed summer session at California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, CA.

1966

Assistant Professor of Sculpture, State University of New York, Buffalo.

1958–66

Exhibited and commissioned to create architectural public artworks.

1967

Awarded teaching scholarship to attend California College of Arts and Crafts.

Moved to California (Oakland, Berkeley).

1968

Received master of fine arts degree from California College of Arts and Crafts (dissertation title: “Energy & Art”).

1967–70

Artistic work during this period included kinetic sculpture, “environments,” light-shows, “happenings,” performance art, and collaborations between artists and engineers.

Taught courses at University of California Berkeley Extension.

Began research and writing about matriarchal Goddess-worshipping cultures.

1969

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) Bay Area chapter coordinator.

1970

Devoted herself to research and writing from a feminist perspective about ancient religions and influence on feminist thought.

1972

Moved to London, where she continued to research and write.

Conducted research at British Museum Library (London) and Ashmolean Museum Library (Oxford).

1972–73

Traveled widely to collect evidence and additional research material for her books: Lebanon—Baalbek, Beirut, Byblos; Greece—Athens, Delphi, Eleusis, Smyrna, Halicarnassus, Rhodes; Crete—Agios Nikolaos; Iraklion, Knossos, Phaistos, Agia Galini, Lato, Chania; Turkey—Ankara, Ephesus, Istanbul, Marmaris, Selcuk, Mersin; Cyprus—Kition, Nicosia, Paphos.

1974

Spare Rib Magazine, London, featured an article by Merlin titled “The Paradise Papers.”

Married again (kept last name “Stone”) and moved to Quadra Island, British Columbia.

Continued research and writing.

1975

Widowed after thirteen months of marriage.

Returned to London, then departed via Heathrow, arriving June 28, 1975, in Miami Beach, Florida, to help her mother care for her father, who had Alzheimer’s disease.

1976

First edition of The Paradise Papers published by Virago Press, England.

Met Lenny Schneir in Miami Beach, and soon after moved into his New York City apartment.

Dial Press obtained rights to The Paradise Papers and republished under new title, When God Was a Woman.

1979

Completed manuscript for Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood and decided to publish using her own alternative press, New Sibylline Books.

1981

Authored a monograph entitled Three Thousand Years of Racism (New Sibylline Books).

1983

Writing included in the Encyclopedia of Religion.

1984

Rights to Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood sold to Beacon Press, Boston.

1989

The Goddess Remembered, a film produced by the National Film Board of Canada, featured Merlin Stone, together with three other feminist pioneers.

1990

Interviewed for New Dimensions Radio, PBS programming, “Return of the Goddess.”

1993

Honorary doctoral degree awarded by the California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco, CA.

1995

Completed writing of unpublished novel, One Summer on the Way to Utopia (aka Dreams of Getting There).

1976–2005

Presented at conferences, workshops, and classes throughout the United States and abroad.

2005

Declining health.

Lenny and Merlin moved to Daytona Beach, FL.

2008

Diagnosed with pseudobulbar palsy.

2011

Merlin passed away on February 23rd, in Daytona Beach, FL, expressing that she had accomplished everything that she wanted to achieve in this life.

[contents]

my life with

merlin stone:

a memoir

The day after Lenny met Merlin,

September 21, 1976, Key Largo, Florida.

A Note About This Memoir

—Carol F. Thomas

Lenny Schneir has written a unique tribute to his partner of thirty-four years. It is part memoir, part love story, reminiscent in many ways of a variety of regional American literary genres. Lenny’s story begins as a coming-of-age narrative, a kid growing up in Kew Gardens, New York City. Filled with anecdotes of typical fifties adventures of the young and the restless, the story relates a magical falling in love, romance, and the transformation of a diamond-in-the-rough gambler by a beautiful artist, scholar, writer, and feminist.

I am not alone in this judgment. Miriam Robbins Dexter, PhD, author of Whence the Goddesses, calls it “a beautiful work of love … celebrating the life of Merlin Stone.” Vicki Noble, feminist shamanic healer and author of The Double Goddess, says, “Lenny Schneir’s tribute to Merlin Stone—her life, her person, her work—touched me to the core.” And I feel compelled to quote Donna Henes, author of The Queen of My Self, who says: “Lenny’s chronicle of [Merlin and] their life together was extremely touching. His adoring vision of Merlin enlarged my admiration and respect for her as a supremely principled person who truly walked her talk and lived her ideals. She was an exemplary role model. May we live up to her shining example.”

But why do I feel I must preface Lenny’s memoir with these words? Because, in fact, at least one prominent feminist declared, “Lenny, you just don’t get it.” She felt a book about Merlin should be authored entirely by women, and that Lenny, though Merlin’s life partner for all those years, really was not the one to praise her. Clearly, I and others strongly disagree. I first met Lenny when I was giving a poetr

y reading at the Casements, a cultural center in Ormond Beach, Florida, near where we both live. I had just finished reading when a tall gentleman approached wearing a brilliantly colored tie-dyed dashiki and bandana. His demeanor was courtly and he was very complimentary of my reading. The poems I read that evening suggested a need for change in the deeply asymmetrical relationship in contemporary American culture and a critique of the patriarchal lexicon, which leaves out any trace of women’s voices, sensibilities, or perspective.

After introducing himself, Lenny told me who he was—the loving partner of Merlin Stone for thirty-four years, the last three spent attending to her as she fought valiantly against a cruel disease that rendered her voiceless and helpless. Lenny asked me if I would help him create a memoir/tribute to his beloved partner. As he told me bits of his story, he could not have known that I was very familiar with Merlin Stone’s landmark books, research, and scholarship in When God Was a Woman and Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood. Her books were crucial in the research for my teaching and writing, as well as that of my students at a number of colleges and universities.

When we met for a second time to discuss Lenny’s project, I was deeply impressed with his breadth and depth of knowledge of very specific and different fields of expertise. He was well known in the world of collectors of memorabilia, and the author of Gambling Collectibles: A Sure Winner, which built his reputation among serious collectors, gamblers, and poker players. As he continued with his narrative, he also revealed the development of a growing appreciation of a wider world that included an admiration of the extraordinary sculptures of his partner and her fame as both artist and art historian, scholar and accomplished author. He also developed a deepened understanding of the voice and heightened sensibilities of the woman, both as artist and partner, a partner who would not suffer male chauvinists easily.

This memoir, which Lenny related to David Axelrod and to me, is genuinely in Lenny’s own voice. We have worked hard to preserve his point of view and even his speech patterns. We did that because the more time we spent with Lenny, the more we saw him as more than just a man who adored and assisted his partner, the famous Merlin Stone. We came to feel that he was, in many ways, a conduit for her energy. At a benefit memorial celebration in honor of Merlin Stone presented by feminist pioneer Z Budapest in September 2011 in Clearwater, Florida, Lenny made a speech—the earliest version of his memoir—that was so heartfelt as to win over nearly every heart in attendance. The memoir you read here is one more of his gifts given with the intention of not just honoring Merlin, but of assuring that her work as a feminist honoring the Goddess will continue.

[contents]

My Life with Merlin Stone:

A Memoir

by Lenny Schneir,

as told to David B. Axelrod with Carol F. Thomas

She was motionless, in what I recognized as a full lotus position. I observed her at sunrise from a distance as the sky gradually lightened, bringing more details into focus. She had long, rust-colored hair that gently flowed over her shoulders and down to the middle of her back. She wore a Levi’s jacket and, just like I did, bellbottom dungarees, even though it was still very warm in Florida. And there she sat—a vision in the quiet Miami Beach dawn.

As she stirred, I made a move of my own and went over to talk to her.

“Where have you been for the last fifteen minutes?” I asked her, curious about her long, quiet posture.

“You wouldn’t believe it if I told you,” she replied, and I truly wouldn’t have understood.

“So what are you doing here?” I pursued.

“I meditate every morning.”

She was receptive, even welcoming, of my advance. She rose to brush the sand off her jeans, put her open-toe sandals back on, and strode up closer to check me out. It was clear she was quite self-confident. I had an eerie feeling she was more the one who was sizing me up than vice versa. I introduced myself.

“Lenny, from New York.”

“Merlin, born in Brooklyn.”

“That’s an unusual name,” I said, wondering what kind of wizard she was. “Are you vacationing down here?”

“I would be in London now except I had to come here to help my mom,” she said with a slightly British accent.

That was September 20, 1976, the moment I first saw and spoke to Merlin Stone. But before I go on about our first meeting, “Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear.” I was not the Lone Ranger, but I knew what a Lucky Strike was: “LSMFT.”

Picture dancing Lucky Strike cigarettes as they intoned, “Lucky Strike means fine tobacco.” That was in the 1950s. Some who look back say those were the good old days when there were real family values. Of course, we were also told how great cigarettes were for us—pleasurable, sexy, even healthy. We were shown the ideal family on shows such as Father Knows Best and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, not to mention I Love Lucy, with Ricky Ricardo’s endlessly scolding and even spanking of Lucy for her mischief. These were the ideal and iconic albeit unattainable families and portrayals of the roles of father, mother, and “above average” children. Not only did father know best, but the wives, and mothers within the family, were to be obedient and subservient helpmates. Oh, those were the good old days.

I was a teenager living in the ’50s, when these were the sacred rules for many families. I lived with my mother and sister in the middle-class New York City neighborhood of Kew Gardens, Queens. My mother was called a housewife, attempting to live up to the ideal portrayal, which our culture mandated. But my father was often absent from our fifth-floor apartment. He was a shoe manufacturer. He and my mother seemed to have a tacit agreement that he did not have to abide by the stereotypical ideals of the American husband.

My father and I had such a distant relationship that I never called him “Dad.” He liked to smoke and drink, gad about—travel, gamble, drive a fancy car. My father wanted to be a bon vivant, living the American dream, but he was completely disinterested in his family. He always worked hard, to the point of being driven. My mother complained to me about my father’s lack of interest in her and the family. Even as she reluctantly acquiesced to the lifestyle he imposed, she continued to hope that he might cease his obvious “escapades.” As a young male myself, I missed having a father figure, though his absence gave me the time and freedom to become my own man.

It hurt me to hear my mother complain. We loved each other and were close throughout our lives. Though I was just a kid, she trusted me with her thoughts.

“I’m a doormat,” she would reveal sadly while seated at the kitchen table in her flower-print housedress. “I wish I had a happy marriage. I don’t understand him.”

“He takes care of us,” I would say, trying to console her, but it was a weak try. I knew that in my father’s eyes, money and status had tremendous importance. But for my mother, money had little meaning. She was searching for his love, so there really wasn’t anything I could say to console her. My mother hoped he would change, but he never did. The result of my father’s absence was that I was a juvenile delinquent in my own mind.

I worshipped James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, Marlon Brando in The Wild One, and everything Elvis Presley. I lived in a Blackboard Jungle of my own creation, which brings me back to LSMFT—Lenny Schneir Means F-ing Trouble. That’s what I told my friends it stood for. I was a twelve-year-old smoker, free spirit, and rebel, antisocial and ready for the gamble called life.

That, at least, was how I wanted to see myself. My mother actually changed the hospital record of my birth—from May 20, 1941, to April 20, 1941—so she could enroll me in school a year earlier. I was what my mother called “a handful.” She didn’t know what else to do with me. That set me on a course of competing with the older boys in my class—acting every bit the clown until I actually got a handle on what would impress them. Thereafter, even before my teens, I was the leader of a small pack of prank

sters and street adventurers. We didn’t do any major harm. We were more mischievous than malicious, though I certainly was a bully to many during that time. As I have grown older and wiser, I realize the harm I caused, for which I am truly sorry.

I learned early on how to manipulate my mother. I did what I wanted. I could escape the apartment whenever I pleased.

“Where are you going?” my mother would naturally ask.

“Down,” I’d say, joking about our living on the fifth floor.

“You’re too young. You shouldn’t be going out,” Mom would say, and then add ironically, “Look both ways, even on a one-way street.”

And off I would go, first to the schoolyard, and then into the world of fun and games. My best friend, Nick, had four brothers, and on Friday evenings I’d go over to his house, where his parents would bring out some worn playing cards and a cigar box full of pennies. They would divide them equally and we would play poker. It was family togetherness, an eight-handed game—seven family members and me. At the end of each session, we all put our pennies back in the box. I almost always lost, but in doing so, I learned to love the game.

Another idea of a good time, around 1955, was to gather some friends and take the subway to the “city,” where we would heckle the street preachers near the Camel sign in Times Square. They’d stand on their soapboxes, a Bible in one hand and an American flag on a stanchion at their side. They would shout their Gospel message to a crowd, and we would stand at the edge driving them crazy:

Merlin Stone Remembered

Merlin Stone Remembered