- Home

- David B. Axelrod

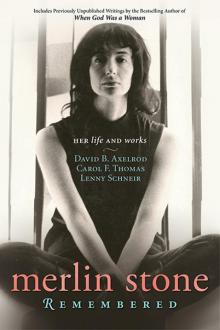

Merlin Stone Remembered Page 7

Merlin Stone Remembered Read online

Page 7

It was only about three months into our relationship when I told Merlin openly, clearly, “I am in love with you. Do you love me?”

“Yes,” she said.

“You know, Merlin, I’m in the Guinness Book of World Records.”

“For what?” she played along.

“For falling in love with you instantly. How long did it take you to fall in love with me?”

“It took me a little longer to unpack my toothbrush.”

She had showed up with little more than a battered mountain backpack. If she had needed to leave, it wouldn’t have taken her long. She was the Ruby Tuesday of the Rolling Stones when I met her, but not because she was irresponsible. Rather, she was open to taking any turn in the road of life she wanted. She had always lived that way.

When Merlin and I lived in New York City, we’d pick places to travel, often just short trips with a rental car. City folks didn’t have to own cars. We would take the subway to the Port Authority Bus Terminal and take a bus to Kingston, New York. We’d have a meal at the diner and make a call to Enterprise Rent-a-Car. They’d pick us up. And, as habit had it, I’d wind up at the wheel, headed toward Phoenicia, New York, where we’d rent a cabin. Phoenicia seemed suitable because it was, after all, the name of an ancient civilization and Merlin, at the time, was fully engaged in writing her next book, Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood.

“I feel like I’m on my honeymoon,” I told her when we would go to the cabin in Phoenicia. We must have rented that cabin at least a hundred times in our thirty-four years together. Merlin, herself, began to call it our “honeymoon suite,” and each time we retreated there, it was our honeymoon all over again. The love and tenderness, the joy and passion we found with each other over the years not only never waned, but it deepened and enriched both of our lives. We were happiest when we were alone together.

Over the years, a person’s greatness can eclipse their real humanity. Merlin always believed that one good indication of intelligence was a sense of humor. She loved to laugh, so I always tried to be funny. She was serious when necessary, but between us, we could get silly. Of course, it was all I could do to try to keep up with her linguistically, but we enjoyed exchanging our unique lexicons.

In Phoenicia, we’d lean over the railing of a bridge, a short walk from our cabin, to watch as people in huge truck innertubes made into platform rafts floated down the Esopus River. They’d bounce off the rocks and fall out of their little crafts, and we’d laugh.

“Man overboard!” I’d shout, even if it was a woman.

“Shall we throw them one of our Life Savers?” she’d ask, reaching for a roll of the candy in her shoulder bag.

“Does that look like fun to you?”

“We’ll jump off that bridge when we get to it.”

“It’s a bridge over troubled waters for me. I’m not jumping in.”

“They are pretty good-looking for tubers.”

“You’re an expert linguini-ist,” I’d tell her, praising her cleverness with words.

We rejoiced in the sunshine, the screams and laughter of the adventurers on the river, our own sense of mirth, and our love for each other. Merlin always said, “Do what’s fun and let it energize and excite you, as long as it doesn’t hurt you or anyone else.” With her, that was the easiest thing I ever did.

For the next two years after we got back from our visit to see her daughters in San Francisco, Merlin was writing Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood. I surprised her with the new technological tool of her time: an Apple II Mac computer. When God Was a Woman and Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood started as notes she took while she traveled—written and carried in her backpack as she researched. Then, she transferred her notes meticulously on a portable typewriter back in London. Merlin infused tremendous energy into the movement for women and men alike, not with conventional methods but with a typewriter. The result, ultimately, has been a victory for all people in search of gender peace and equality.

In our apartment, where she had carved out the front of our two rooms as her own place, she sat at a long, old wooden claw-footed table—not a desk, but a wide space to spread out on, books and all.

The room was lit by a chandelier I had reclaimed from a dumpster. It was crystal, with marble-sized balls on strings, positioned exactly over her table. She had a heavy, old wooden desk chair with arms to help her rest while taking a healing breath. She worked there for hours at a time. When Merlin moved in, she opened the shutters I had kept closed. I lived on the parlor floor and didn’t want folks looking in. My friends named my apartment “the morgue” when I lived there alone.

Merlin opened those shutters to the street, literally bringing warmth and sunshine into our lives. She watched the world walking and driving by as she wrote, immersed in her routine. Awake at perhaps 7:00 am, she would make herself a cup of black coffee with sugar, light up a cigarillo, sit down by 7:30, and work for hours.

Often, if I had been playing poker or buying and selling collectibles, I would come home at very odd hours and find her working on the word processor with ideas she had for her books and articles. I’d wake up to her saying, “Let’s hit the Vandam,” and we’d go out for an hour of lunch or dinner. My being employed away from home gave her an undisturbed place to work. We’d return from our meals and she would joyously go back to her writing. Later, to my delight, she might just put her head on my shoulder. But best of all, when she was finished writing, we’d have only each other.

We would walk three blocks to our favorite haunt, Washington Square Park, and sit near the chess tables where I knew many of the players. When we strolled over to the people playing Scrabble, Merlin was well known there. My friend Josh, one of the best Scrabble competitors in the city, worked at the Strand Book Store. He knew who Merlin was and spread the word.

“Look, that’s Merlin Stone,” he’d whisper to the other players as she approached. “She’s the author of When God Was a Woman.”

Merlin didn’t want to be a celebrity, but people in the neighborhood learned who she was and they would speak to her. She’d be on the bench in front of our house, and two women would regularly invade her space with their presence along with two cups of coffee so they could sit and talk with her. Even the old Italian women in the neighborhood, sitting on their bench as we walked by, would poke each other and say, “That’s her.”

Merlin and I often went to many other locations, usually by bus or subway—Central Park, Battery Park, South Street Seaport, the financial center, the Hudson River piers, and eventually almost every NYC park. We’d always hold hands. I was holding on to her for dear life.

We walked all over lower Manhattan. We visited museums where she was completely fluent about the artists, the art, the antiquities. She knew every style because she taught art history. She knew the stories at every special museum: the National Museum of the American Indian, the American Museum of Natural History, the Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Jewish Heritage, and so many more. We probably hit them all, and she could have been their tour guide. An extraordinary memory alone does not explain what Merlin knew.

We watched people. I dressed in tie-dyed clothes or fancy Western shirts—still do—and folks noticed. As they approached us, Merlin would lean toward me and say, “Here comes another compliment.” Sure enough, someone would say, “Hey man, I love your outfit.” Some Merlin had made for me, sewing everything with a needle and thread. We were a groovy couple.

Merlin did not need to dress up to be gorgeous. She actually seemed to disguise her natural beauty. She wore Levi’s jeans tucked into knee-high, low-heeled boots—sometimes low-cut Converse sneakers—for the first fifteen years we were together. She usually wore shirts she had made herself, along with a flat-topped, brown suede hat and tinted glasses. In the winter, she wore her peacoat.

A story about the peacoat! She came to New York to live with me on October 1

, 1976, with just her mountain backpack. She had no coat and the weather was getting cold. Imagine, she was that far along in her life and all she had or wanted at that moment fit into her backpack. She said, “I need a coat.”

“We can go uptown,” I suggested, thinking something fashionable.

“I’m thinking peacoat.”

Bloomingdale’s was selling reproductions for a fancy price as a new fashion trend.

“Do you know where there’s an army-navy store with used items?” she asked.

I knew one close to Canal Street. The peacoat she bought that day for eight bucks lasted for more than twenty years. She never desired or needed fancy things. She would save the shards of soap and make them into a larger bar and wash her clothes in the tub. In her travels, she learned how to wash her clothes in rivers, streams, creeks, or even puddles. She shopped for the least expensive items, purchased at the stores on Broadway, Canal, or Orchard Street where they had bargain bins out on the sidewalk. It wasn’t because she was cheap as much as she didn’t need to prove anything. She was a minimalist. The less I spent, the more she loved me.

“A true believer needs nothing and has everything,” she told me. She simply bought only what she needed to survive. Merlin was a waste-not-want-not person. In fact, it was only days later that I told her, “I’m going to Angelo’s for a haircut.”

“You don’t have to go to Angelo. I’ll cut your hair.”

“You know how to cut hair?” I asked.

“Of course, I know.”

“Okay,” I told her, “I’m a gambler. I’ll take a chance.”

“Let’s go outside to our bench,” she instructed me, picking up scissors, a hand mirror, and a plastic bag. She already had declared a city bench to be ours in Father Fagan Park right in front of our apartment. There, she sat me down and asked, “How do you want it?

“Keep it long as possible, but neat. Trim behind the ears and shape the beard.”

She took a snip. She held on to the hair and put it in the plastic bag so she didn’t create any litter. Snip. Snip some more. She took her time. The process took at least thirty minutes. Merlin never rushed anything. When she finished, she showed me her work in the mirror.

“Fantastic,” I said, and I meant it. “How did you do that?”

“I’m a sculptor,” she revealed. Not only was that true, it was a major understatement. That was an important accomplishment I had never heard about until then. She didn’t brag. She had nothing to prove to me.

In warmer weather, we’d go out together and, from the way she dressed, you wouldn’t have known she was the influential and renowned author I was getting to know. She often wore tights, moccasins, and a black top she had made for herself with straps that were loose and comfortable. In the mornings, I loved to watch her get out of bed and get ready for work. Every move she made was a visual symphony to me.

“I’m on a schedule,” she would say.“See you later. Sweet dreams.” Just holding her hand, kissing her, touching her skin, hugging her, absorbing her words, and looking into those expressive, brown eyes was paradise.

Early in 1976, Merlin completed The Paradise Papers: The Suppression of Women’s Rites. The publisher was Virago Press, in association with Quartet Books in London.

“They found me,” she loved to say. “Things are constantly being dumped in my lap.” And, indeed, she attracted innovative ideas and creative people, always working for a better planet. She was guided, I witnessed, by her Goddess. When I met her in September 1976, the book was selling well for what it was—a mid-level publisher in England, circulating what was, they believed, a “women’s tract.”

Shortly after Merlin moved in, she gave me a copy of her book. I could barely read it. It was much more than I could handle given the habitual anti-academic life I had cultivated. I just wasn’t ready for that type of information. I was the kid who heckled street preachers. I didn’t believe in God, much less a Goddess. But others could see the treasure for what it was. The Virago edition of The Paradise Papers appeared in March 1976, which was just six months before we met. In December 1976, Dial Press contracted to republish the book as a hardback with its new, celebrated title, When God Was a Woman. The title came from lines in the opening chapter of the book: “At the very dawn of religion, God was a woman. Do you remember?”

In early 1978, Harcourt Brace & Co. published it as a soft-cover edition, which immediately began appearing on bestseller lists. When God Was a Woman had begun to change the world.

Merlin increased her energy, giving lectures and visiting bookstores. When she came home from her initial publisher’s book tour, she said, “I can do this better myself.”

Thereafter, she went to women’s bookstores and women’s studies groups—even before there were many women’s studies programs. Being Merlin Stone, she had developed an extensive network of contacts within the women’s movement. She was so proud and amazed at the progress of When God Was a Woman. Prior to her work, women’s studies courses consisted primarily of the history of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century suffrage movement. Merlin’s seminal publication helped inspire a shift from political issues to include spiritual feminism. The role of religion in establishing and maintaining patriarchy became a part of women’s studies courses.

I watched Merlin sit on the edge of our bed and dial her mother with the good news. The conversation I overheard was truly a moving moment between Merlin and her mother, as it revealed the difference between the older generations of women. There had been a true shift in women’s expectations, perceptions, and values.

“Mom, the book I wrote has come out in the U.S. They even gave it a better title, When God Was a Woman.”

“How much did they pay you?” her mother asked.

“It’s about much more than the money, Mom.”

“But they paid you, didn’t they?”

I watched as her whole demeanor changed when she realized that her mother, like so many women of that generation, didn’t understand the importance of Merlin’s feminist work. I could tell that her mother’s response to the news hurt Merlin, and she brought it up several times later in our lives. She felt that, as much as she and her mother loved each other, her mother was just from a generation of women who found it hard to understand what Merlin was doing.

Her father supported her early interest in art. She adored him. She started to sculpt when she was eight or nine. Her brother recalled that she had received the first sculpture award issued by her high school, Erasmus Hall. It had the largest student body of any high school in the country, and thereafter, they always gave an annual sculpture award.

Merlin redoubled her efforts toward completing her new book. She spent over two years on its composition. Ancient Mirrors of Womanhood was published in 1979.

“I’m going to self-publish,” she informed me. “I found a printer in Wisconsin. Cynthia is doing the artwork. It will cost a buck a book for 3,000 copies.” New Sibylline Books was born.

“When do you need the money?” I asked her, literally jumping up to go get some cash. Would I ever hesitate? I was so happy to contribute. In fact, this was the beginning of my spending much more quality time with her—running errands to the post office and back and buying shipping supplies. I was helping to set up her business. This was a new calling for me.

It took only a couple of months for her to produce the actual physical book. She did everything thereafter—the layout, front and back cover design, fliers, mailers, publicity, bookmarks to hand out. The orders for the book came almost immediately. Merlin, directed by her Goddess, as always, knew exactly what to do. This was a pre-digital world, so she kept records in handwritten notebooks and files. She packed and addressed boxes. Fifteen thousand copies sold in just five years, all sent from our two-room apartment. Merlin was her own lawyer, reading and negotiating publishing contracts. She was her own manager and agent, distributing he

r new book even as she was still traveling and lecturing to introduce When God Was a Woman to an eager audience.

In 1984, Beacon Press, located in Boston, was alerted to the success. They characterized the initial sales as just testing what they called the “hardcore market.” That meant—and they were quite right—that when they republished it with their mass marketing, it would find the hundreds of thousands of women internationally who needed to know what Merlin was writing. When God Was a Woman, at the time of this writing, has sold an estimated one million copies and has been translated into four languages.

“How did you do it?” I often asked. I actually asked her this hundreds of times through the years. Her quest was astounding to me—beyond my love, comprehension, and admiration for her.

“I had help,” she would state clearly, and then she would add, “I was guided.”

“Who guided you?” I would ask incredulously.

“It isn’t like one person or another,” she would try to explain. Merlin had no specific name or image for her Goddess. “I feel there is something inside me. It’s an inner understanding.”

“What do you understand?”

“It’s a voice. It’s like a female energy in the universe.”

“Can you tell me what she says for you to do?” I simply didn’t understand.

“As long as I’m willing, then the direction She guides me is the correct path that I should travel. It feels like I’m being gently pushed or pulled into situations that need to happen.”

“Do you feel like you are being told to do these things?” I would ask, concerned that she might be trapped by some kind of compulsion.

“It feels natural. The Goddess wants it done.”

I wish I had been able to comprehend what she was saying at the time. I know it isn’t only “a woman’s thing.” And as much as I believe it’s true that women see the world in a different way, often more clearly than the way men see things, I know Merlin had a gift. She could hear, intuit, and actualize the energy of her creator.

Merlin Stone Remembered

Merlin Stone Remembered